Editor’s Note: This is the second installment in AJP’s Seongsu series, which examines how Seoul’s former factory district transformed into a global hub for pop-ups, brand experiences and new forms of urban consumption.

SEOUL, February 12 (AJP) - In Seongsu, a former industrial district in eastern Seoul, retail space is no longer leased mainly to sell goods.

It is rented — by the day or the week — to buy attention.

Over the past decade, short-term pop-up leases have replaced the two-year commercial contracts that still define most of the city’s retail landscape.

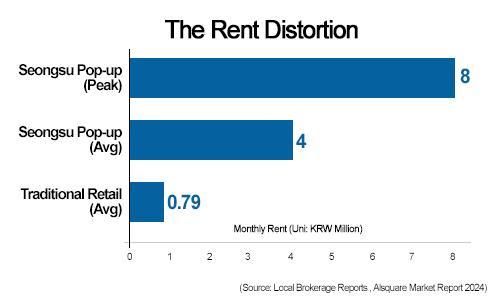

In prime pockets such as Yeonmujang-gil, a large venue of about 900 square meters (around 270 pyeong) can now cost between 100 million and 200 million won (,000–0,000) for a single week, according to 2024 market data from local brokerages and industry reports.

If booked continuously, that translates into a monthly equivalent of 400 million to 800 million won (0,000–0,000).

By contrast, the effective monthly rent (E.NOC) for traditional retail and office space in Seongsu stood at about 290,000 won per pyeong in 2023, according to the 2024 Seongsu Office Market Report by commercial real estate data firm Alsquare.

The widening gap illustrates what analysts describe as a “decoupling” of asset value from retail fundamentals. A parallel market has emerged, where short-term “event leases” are priced not by expected shop sales, but by brand demand, seasonality and promotional timing.

A Market That Runs on Weeks, Not Years

This structure remains unusual in Korea, where stability has long been the defining feature of commercial leasing.

“Contracts like those in Seongsu are very rare,” said Lee, a building owner who manages several properties in the capital. “Most places in Seoul are leased on a minimum two-year basis. Seongsu operates on completely different rules.”

Those rules are shaped by flexibility — and by scarcity.

“Most pop-ups here run on very short terms, from a single day to a few weeks,” said Kang, a Seongsu-based broker. “Everything is negotiable. But if you want to open for just one or two days, it’s extremely expensive. Daily rates often start from around 10 million won and rise quickly depending on demand.”

For landlords, the appeal is clear. Short-term leases allow them to capture peak-season premiums that long-term tenants cannot match. For brands, the costs are justified as marketing investments rather than rent.

A Global Outlier

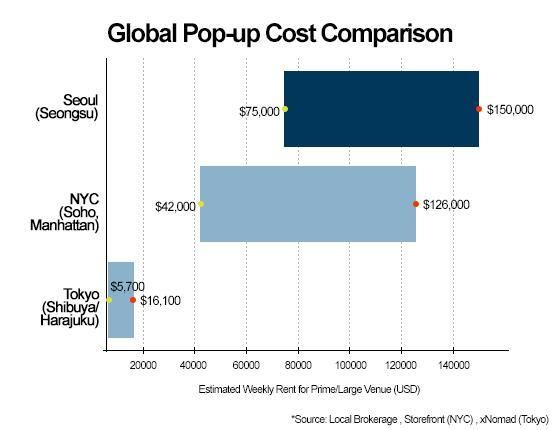

By international standards, Seongsu’s pricing has reached striking levels.

In Tokyo’s Shibuya district, pop-up spaces typically start at around 920,000 yen (,700) per week for smaller venues. In New York’s Soho, prime Broadway retail rents average about 6 per square foot annually, translating to roughly 5,000 per week for a comparable 900-square-meter space.

At its peak, Seongsu now rivals both.

In many cases, transactions bypass conventional real estate brokers. Large venues operate as registered event spaces, signing short-term venue-hire agreements directly with brands, blurring the boundary between retail, exhibition and entertainment.

For marketers, the rationale is straightforward.

“Pop-ups are not about making money from sales,” said Lee Seung-hwan, head of FIG, a creative agency. “They are about branding. Once you add production, design and staffing, budgets can easily reach hundreds of millions of won.”

The Economics of “Digital Bricks”

Beyond weekly venue fees, interior construction alone often reaches about 1 billion won (0,000) for high-end pop-ups — all written off over just two or three weeks of operation.

Unlike conventional stores, where fit-out costs are depreciated over years, Seongsu pop-ups treat the entire investment as a one-off marketing expense.

According to digital marketing firm Inquivix, the primary performance indicator is the “Offline-to-Online (O2O) Loop,” tracked through spikes in Naver searches, social media mentions and map “saves,” rather than in-store revenue.

The physical space functions as a content studio — a place to generate what marketers call “digital bricks,” visual assets that build a brand’s online presence long after the pop-up closes.

High Rewards, High Risk

For smaller brands, however, the boom resembles a high-stakes gamble.

“A lot of founders dream of opening a pop-up in Seongsu at least once,” said Yoon, a clothing brand owner in her 30s. “It’s a powerful way to introduce your brand. But everyone knows how expensive it is. Only companies with strong backing can really afford it now.”

Rising costs have gradually narrowed participation to large domestic labels, global luxury brands and well-funded startups.

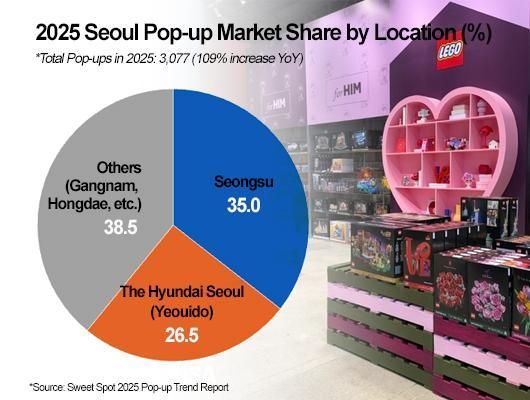

According to the 2025 Pop-up Trend Report by Sweet Spot, the number of pop-up stores in its network jumped 109 percent in 2025 to 3,077, with Seongsu accounting for about 35 percent.

What began as a fashion and beauty marketing tool has expanded into technology and finance. Data and crypto-related firms such as Palantir and Upbit have used Seongsu pop-ups to turn abstract services into physical experiences.

Foreign Foot Traffic Fuels the Premium

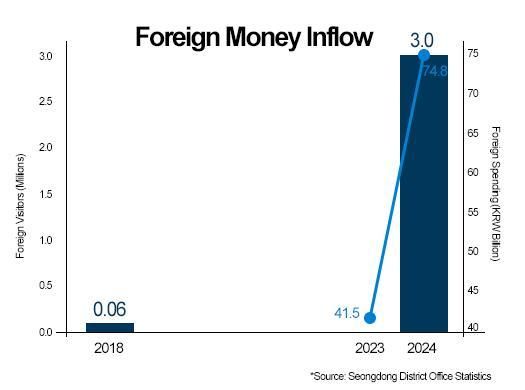

Foreign visitors have helped sustain the surge.

Data from the Seongdong District Tourism Survey show that Seongsu’s foreign visitor count rose from about 60,000 in 2018 to roughly 3 million in 2024. Spending by foreign tourists in the district reached 74.8 billion won ( million) in 2024, up 1.8 times from a year earlier.

“Even when daily rent runs into the millions of won, it can still make sense,” the broker said. “Foreign customers lift overall sales.”

The leasing boom has fed directly into asset prices. Land values in Seongsu rose from about 40 million won per pyeong in 2018 to around 140 million won in 2023, according to Alsquare — more than a threefold increase.

Analysts describe the result as a new phase of gentrification, in which long-term neighborhood businesses are pushed out by short-term marketing installations.

For visitors, the spectacle often conceals the economics.

“I just enjoy going to Seongsu to see what’s new,” said Lee Min-joo, a Seoul resident in her 30s. “I didn’t realize how much money goes into these places. But the interiors, scents and atmosphere stay in your memory. I almost map which brand was where.”

That reaction captures Seongsu’s transformation.

The district is no longer priced like a retail neighborhood. It is priced like media time — sold in short slots, bid up by competition, and justified by reach rather than receipts.

Copyright ⓒ Aju Business Daily 무단 전재 및 재배포 금지