The Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism’s 731.8 billion won content policy fund, announced last month, immediately drew the industry’s attention. Coupled with the ambitious vision of a “300 trillion won K-culture era,” the plan was widely read as a clear signal that the government intends to place the content industry at the forefront of national strategic industries. Its status as the largest fund ever carries symbolic weight in itself.

What distinguishes this policy is its focus on expanding financial structures beyond direct production support. Built around the Fund of Funds and subdivided into IP, exports, cultural technology, new growth sectors, and M&A and secondary funds, the framework resembles an attempt to reorganize the content industry into a self-circulating investment ecosystem. The intent is to narrow the gap between box-office success and industrial fundamentals.

At the core of the initiative lies the expansion of large-scale IP funds. Competitiveness in the content industry ultimately derives from intellectual property, yet domestic production companies have long struggled to retain IP over the long term due to financial pressure. By allowing continued investment in the same company, the new structure offers a financial solution aimed at turning IP into an accumulable asset. In this sense, it marks a meaningful shift from a production-centered model to an asset-centered one.

For IP funds to translate into genuine structural improvement, however, exit strategies must also be aligned with a long-term perspective. If pressure for quick returns dominates, production sites will inevitably tilt back toward short-term hit-driven strategies. Sustained world-building and character expansion require capital that is patient by nature.

Export-focused funds are presented as a tool to accelerate the outward growth of K-content. Korea’s global presence has already been proven, but dependence on overseas platforms remains strong in distribution and licensing structures. While financial support can expand overseas reach, it may not substantially alter profit-sharing arrangements unless bargaining power improves as well. Expanding export volume and securing industrial leadership are separate challenges.

The creation of a cultural technology (CT) fund can be read as a move toward industrializing production environments. Virtual production, AI-based workflows, and immersive content technologies are rapidly becoming global studio standards. Technology gaps translate directly into differences in cost efficiency and production quality. Investment in this area signals a strategic transition from labor-intensive structures to technology-driven ones.

The challenge lies in the long-term and uncertain nature of technology investment. Whether policy finance can remain committed to fields that take time to yield visible results will determine success. If fund management prioritizes short-term returns, capital is likely to flow toward proven areas rather than experimental technological development.

New growth funds are designed to focus on early-stage startups and promising sectors such as games and webtoons. From the standpoint of broadening the industrial base, this is a positive move. Yet these areas already attract active private investment. If public funds crowd out private capital, the anticipated ripple effects may diminish. Government funding is most effective when it fills genuine market gaps.

The establishment of M&A and secondary funds aims to shore up a previously weak exit market. Content companies have faced structural constraints in attracting investment due to limited exit channels after growth. An active exit market could lay the groundwork for virtuous investment cycles. At the same time, it may widen pathways for promising firms to be absorbed by foreign capital, raising concerns about industrial sovereignty.

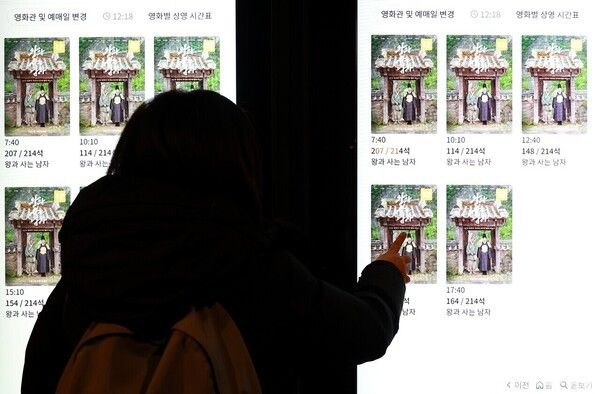

Expanded support for the film sector carries a more urgent, stopgap character. Raising the government’s contribution ratio to 60 percent reflects the reality of shrinking private investment. Larger main investment funds and support for mid- to low-budget films and animation function as safeguards for industrial diversity. Still, amid declining audiences and the weakening of theater-centric revenue models, increased production alone does not guarantee recovery.

Incentive reforms aimed at attracting private investment were also introduced. First-loss coverage, excess return transfers, and expanded call options are effective tools for fundraising. Yet if the government repeatedly shoulders greater risk, investment discipline may weaken. Given the high volatility inherent to the content industry, professionalism and accountability in fund management become even more critical.

Ultimately, the success of the policy hinges on operational competence. Which managers are entrusted with capital, how projects are selected, and how rigorously post-investment management is carried out will determine real outcomes. If operators pursue only stable revenue models without fully grasping the policy’s intent, capital is likely to continue concentrating on popular genres and proven formats.

The goal of a “300 trillion won K-culture” cannot be achieved by declaration alone. Only when IP is held long term, recurring global revenues are generated, production efficiency is enhanced through technology, and stable exit structures are secured can the industry naturally expand in scale. Policy funds matter as capital inputs toward that direction. More important than the size of the numbers is the imprint such capital leaves on industrial structure and sustainability.

Reported by News Culture M.J._mj94070777@nc.press

Copyright ⓒ 뉴스컬처 무단 전재 및 재배포 금지