In 2024, South Korea officially replaced the term “cultural properties” with “national heritage,” signaling a policy shift away from preservation alone toward broader use and public engagement. On the ground, however, the reality inside the cultural heritage trade tells a different story. Antiquities dealers and field experts say outdated regulations, administrative blind spots, and deep-seated social prejudice continue to undermine the market, raising concerns about the long-term sustainability of K-Heritage.

Billions for Contemporary Art, Pennies for National Treasures

“What happens if a national-treasure-level artifact is discovered at a construction site, but halting construction causes massive financial losses?”

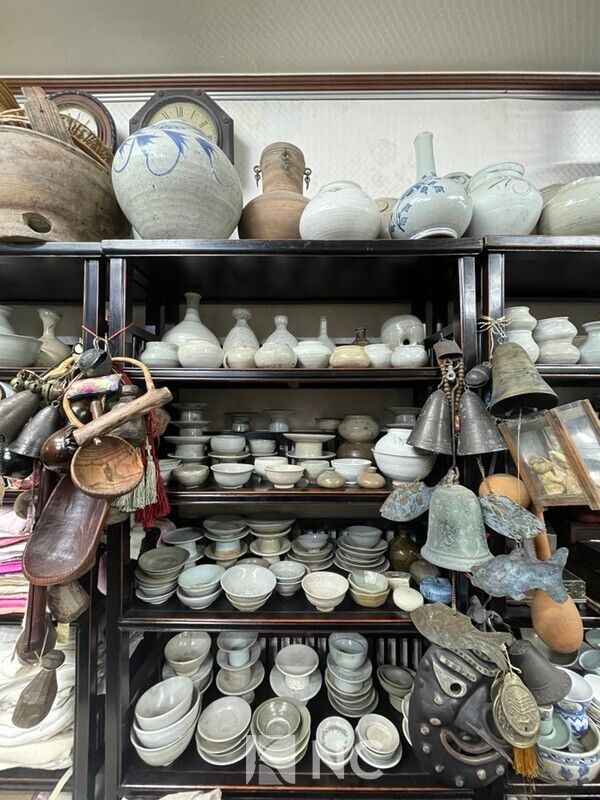

The question, posed by a veteran antiquities dealer, exposes what many describe as the market’s core distortion. While contemporary art by star artists routinely sells for tens of billions of won, artifacts embodying centuries of Korean history often trade for a fraction of that value.

“The current market price of national-treasure-level artifacts is irrationally low,” said one merchant at the Dapsimni Antique Art Market. “Without economic value, public interest fades, and preservation loses its momentum.”

For decades, Korean society has largely avoided discussing the economic value of cultural heritage, treating it as taboo. Critics argue that this mindset has fueled a vicious cycle, where undervaluation leads to neglect, and in extreme cases, the concealment or burial of unearthed artifacts at construction sites.

Experts stress that a shift in public perception is essential. Cultural heritage, they argue, must be recognized not only as something to protect, but also as an economic asset capable of sustaining preservation through responsible circulation. Efforts to develop heritage-centered tourism, including surrounding infrastructure and amenities, are often blocked by rigid preservation-only narratives.

Appraisal Reform Needed, But Training Support Disappears

Restoring economic value depends on restoring trust, beginning with a credible appraisal system. Market confidence, experts say, cannot be rebuilt without resolving persistent doubts over authenticity.

Calls are growing for a governance model that integrates data-driven scientific analysis with the seasoned judgment of experienced field appraisers. Lee Myung-seon, head of academic affairs at the Korea Institute for Traditional Art Convergence Promotion, emphasized that appraisal processes must extend beyond theory-focused academics.

“Field experts with extensive experience in authenticity assessment need to be directly involved,” Lee said. “Only then can we build a verified database of genuine works and establish objective grounds for valuation.”

Despite these demands, government support has moved in the opposite direction. Industry officials say the government eliminated the entire professional training budget for licensed heritage dealers last year, citing the small number of beneficiaries. Critics argue the decision removed one of the few safeguards against illegal trade and weak appraisal capacity.

Regulatory Ambiguity and a Shrinking Administrative Backbone

Regulatory confusion further complicates the market. Dealers are required to document transactions with photographs, yet the defining criterion, whether an item was produced more than 50 years ago, is often impossible to verify due to the lack of reliable dating evidence.

Institutional contradictions also persist. While the statute of limitations for crimes such as possession of stolen goods extends to 10 years, dealers are required to retain transaction records for only five years, leaving traders exposed to legal uncertainty.

Perhaps most alarming is the shortage of enforcement personnel. The National Heritage Administration’s investigative unit reportedly consists of just three to four officials nationwide, a figure widely viewed as inadequate. As responsibilities expanded under the National Heritage system, staffing remained locked in an outdated, enforcement-centric framework.

Hong Sun-ho, director of the Korea Institute for Traditional Art Convergence Promotion, called for structural reform. “A dedicated organization is needed to systematically foster the heritage circulation market,” he said. “If the transition to the National Heritage system is to be more than symbolic, field expertise must be recognized, and genuine public-private governance must be established.”

Reported by News Culture M.J._mj94070777@nc.press

Copyright ⓒ 뉴스컬처 무단 전재 및 재배포 금지