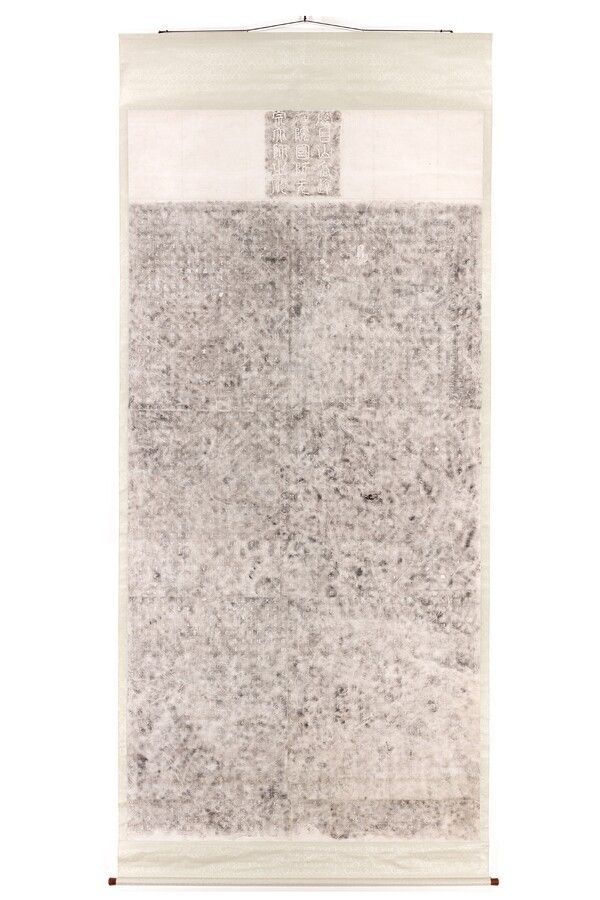

The stele rubbing of State Preceptor Chanyu of Godalsa, later honored with the posthumous title Wongjong by King Gwangjong of the Goryeo Dynasty, is a paper artifact that conveys the depth and texture of early Goryeo Buddhism, intellectual life, and record-keeping culture. Though transferred onto paper, the rubbing preserves the weight of time through dense ink impressions that retain the presence of the original inscription.

Created during the Japanese colonial period, the stele rubbing reflects an effort to preserve the contents of the original stone monument amid concerns over damage and loss. At a time when Korean cultural heritage stood between exploitation and documentation, the act of producing a rubbing became a means of safeguarding form and meaning. The ink left on paper functions not merely as a reproduction, but as a record shaped by historical urgency.

The original stele commemorating State Preceptor Chanyu was erected at Godalsa Temple, located in present-day Yeoju, Gyeonggi Province. While the temple itself no longer remains, the site is now known as the Godalsa Temple Site. Today, the stele’s capstone and base stone remain at the site as Treasure No. 6, while the main body of the stele is preserved at the National Museum of Korea. This divided state of preservation reflects the modern history experienced by Korea’s stone cultural heritage.

The inscription records the life of Chanyu in detail, from his family background and birth to ordination, religious practice, teaching activities, and passing. More than a biographical account, the text reveals the position Buddhism occupied within society and the state during the early years of the Goryeo Dynasty. Through references to royal recognition and institutional roles, the stele shows how Buddhism functioned as a public force in the process of state formation.

One of the most notable aspects of the inscription is the clearly defined division of labor involved in its production. The text was composed by Kim Jeongeon, written in full by Jang Danyeol, and engraved by Lee Jeongsun. This reflects inscription-making practices established after the Unified Silla period, in which composition, calligraphy, and engraving were treated as distinct professional domains.

The fact that the engraver’s name was recorded holds particular significance in East Asian cultural history. Such acknowledgment is rare in comparable Chinese inscriptions and illustrates how Goryeo society recognized technical skill and labor as part of the historical record. Artisans were not anonymous figures, but active participants whose work was deemed worthy of remembrance.

The calligraphic style and layout of the inscription further enhance its value. Written in regular script, the characters are carefully arranged within square grids, reflecting the aesthetic discipline and standards of early Goryeo calligraphy. Order and balance govern both the visual form and the structure of the text, demonstrating the maturity of the period’s writing culture.

Despite damage to portions of the original stone, the stele rubbing remains legible enough to allow detailed study. As such, it serves not merely as a reference image, but as a substantive source for research into early Goryeo Buddhist figures, temple history, and the relationship between the state and the monastic community.

The stele also reshapes the understanding of Godalsa itself. More than a regional place of practice, the temple functioned as a space where the authority and memory of eminent monks were publicly inscribed. Through the stele, Godalsa emerges as a cultural site in which belief, power, and remembrance converged.

Classified as Calligraphy and Painting – Rubbings – Inscriptions, this artifact demonstrates a world in which writing becomes form. Characters extend beyond semantic meaning to create visual order, while sentences structure historical understanding.

Ultimately, the stele rubbing of State Preceptor Chanyu of Godalsa transcends its material form. It is a layered record in which early Goryeo Buddhist thought, the maturity of record culture, collaboration between literati and artisans, and modern perceptions of cultural heritage intersect. The ink impressed upon paper is not simply a copy of stone, but a trace of time preserved against disappearance.

Reported by News Culture M.J._mj94070777@nc.press

Copyright ⓒ 뉴스컬처 무단 전재 및 재배포 금지