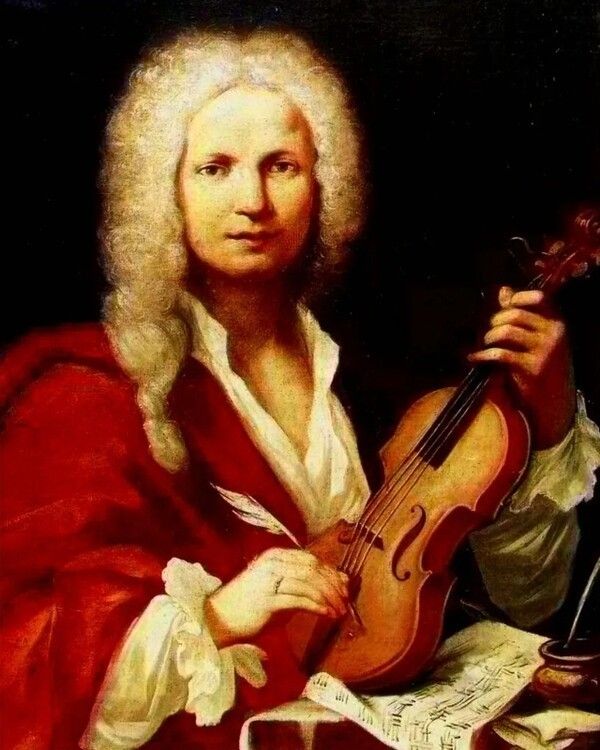

Like the stillness before lightning in suffocating midsummer air, “Summer” from Antonio Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons approaches the listener not with beauty, but with tension. Shaped by the blazing Venetian sun, his frail body, and the unstable atmosphere of his time, this music transcends seasonal description and reveals the fragility of human existence. “Summer” is not scenery but emotion, not nature but destiny itself.

In 1725, Vivaldi published twelve concertos under the title Il cimento dell’armonia e dell’inventione, of which the first four became known as The Four Seasons. Among them, “Summer” bears the most violent and unstable character. If “Spring” celebrates vitality, “Autumn” rejoices in harvest and abundance, and “Winter” embodies cold stillness, then “Summer” is the season of tension, forever on the brink of collapse.

The Venetian summer was filled with humidity and oppressive heat. The water of the canals warmed, and the entire city sank into sticky air. For Vivaldi, who suffered from asthma, such a season must have been closer to terror than discomfort. Breathing itself became a burden, and this physical reality helps explain why his music sounds so nervous and sharp.

The first movement, Allegro non molto, opens with rhythms that feel exhausted and slack. Humans, animals, and fields all seem drained of energy. Birds sing, yet even their voices lack serenity. The violin imitates the cuckoo, turtledove, and goldfinch, but soon a rising wind foretells conflict and disturbance. The music holds both the heavy air under the sun and the anxiety before an approaching storm.

This scene stands in stark contrast to “Spring.” Where “Spring” sings of life with transparent rhythms and bright harmony, “Summer” depicts a world already burdened with fatigue. Vivaldi transforms nature into a metaphor for emotion, assigning each season a completely different psychological landscape.

The second movement, Adagio e piano, represents a summer night. It portrays a human being unable to sleep amid heat and swarming insects. There is rest, but it is not peaceful repose. It is a fragile suspension, always on the verge of awakening. The exhaustion and irritation of the day continue to tremble within the silence of night.

The sudden insertion of Presto e forte is sharp like the sign of an impending storm. Just as thunder and lightning erupt without warning, the music abruptly heightens tension and shakes the listener. Summer is portrayed as a season that prepares explosion even within calm.

The third movement, Presto, reveals nature’s fury in full force. Thunder roars, hail pours down, and crops and fruits are destroyed. The violent tremolo of the violins turns the storm sweeping across the fields into sound. In this summer, there is no mercy. Nature is ruthless.

The face of summer also contrasts strongly with that of “Autumn.” If “Autumn” celebrates wine, dance, and the joy of hunting, “Summer” shows how such abundance can collapse in an instant. The seasons may rotate, but crisis is always hidden within their cycle.

Compared with “Winter,” the character of “Summer” becomes even clearer. Winter is cold and harsh, yet it also contains quiet moments of warmth by the fire. Summer, by contrast, allows no rest even in its heat. It is a season where burning air and storms coexist.

Vivaldi’s own life mirrored this instability. Though ordained as a priest, he was more deeply devoted to music. He entered the world of opera, tasting both success and failure. His life remained suspended between ambition, tension, and fragile balance.

At the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice, he gained fame composing for orphaned girls. Yet his passion for opera drew him beyond the city. The pursuit of grand stages and financial reward eventually led him to bankruptcy and decline. Like a summer storm, success did not stay long.

In his later years, Vivaldi moved to Vienna, relying on Emperor Charles VI. After the emperor’s sudden death, he was left without support and died in poverty and illness. The scene resembles the barren landscape left behind after the storm in the final movement of “Summer.”

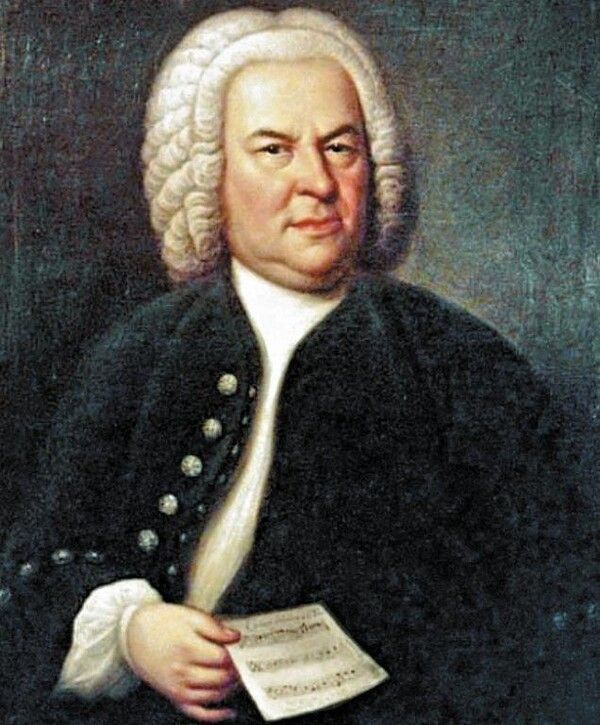

It is ironic that Vivaldi’s music was forgotten for a long time. In the early twentieth century, however, works of Vivaldi arranged by Johann Sebastian Bach were rediscovered, bringing his music back into the light. From that moment, “Summer” of The Four Seasons began to sound again.

What we hear today in “Summer” is not merely the sound of a season, but a record of human tension and fear before nature and fate. With only violin and strings, Vivaldi shaped these complex emotions into persuasive musical form.

Thus, The Four Seasons is not nature music but human narrative. Among them, “Summer” captures the moment when life becomes most precarious.

The summer Vivaldi lived through must have been filled with pain, passion, and anxiety. Those experiences seeped into his music, continuing to strike the listener’s ears and heart like a storm.

Vivaldi’s summer is not a past season. It resembles the recurring crises of life itself. That is why, when we listen to “Summer” today, we hear beyond the sound of nature and encounter the destiny of humankind.

Reported by News Culture M.J._mj94070777@nc.press

Copyright ⓒ 뉴스컬처 무단 전재 및 재배포 금지

본 콘텐츠는 뉴스픽 파트너스에서 공유된 콘텐츠입니다.